I’ve realized lately that I’m low-key obsessed with etymology. The other day, I remembered a factoid I learned in school about how English, in spite of not being a Latin language, owes around 60% of its vocabulary to it (whether this is true or not I do not know and don’t feel in the mood to verify). I challenged myself to think of an English word that comes from Latin (never said I wasn’t a loser) and couldn’t, which frustrated me — “I’m not helping myself prove the point.” And there I had it: “point.” I know that word comes from Latin because I speak three other Latin languages that have it: “punto” in Spanish, “ponto” in Portuguese, and “point” in French (though in their case it’s pronounced “poo-ahn,” ending in a nasal sound I’ve found English speakers incapable of reproducing).

The two common definitions of “point” in English seem to be unrelated: the graphic one (a point in a map) and the linguistic one (a point in an argument). And yet, I figured, there must be a connection, and that connection would elucidate the original word. In Spanish, “punto” means both “period” (at the end of a sentence) and “dot” (in a dotted line) — and this still has echoes in English, for example, in the expression “dot com,” something that should rightfully be called “period com” because English speakers don’t call periods “dots” in any other circumstance (they do say “exclamation point” or “punctuation,” though). This shows up as well in the expression “on the dot” to refer to an arrival that is—wait for it—punctual, probably because the hands of the clock are hovering over a specific dot at that time. Point, dot, period: what do they all have in common? Their shape and size, produced by—wait for it again—a pointy object. That has to be, I figured, the root. Probably the word “punctum,” which must mean “tip” or something like that — hence, for example, the word “puncture” to indicate a cut caused by something pointy.

But that was only one of the definitions. To make sure, I tested the other (and at this point, I was fending off the urge to Google). The idea of “puncture” made me think that maybe the original sense of “point in an argument” came from “point in a sport” — and that sport was probably fencing or something, where the tip of a sword touched/cut the opponent, scoring a “point.” Since debating is a sort of fencing but with words (just go with it), then a winning argument would be a “point.”

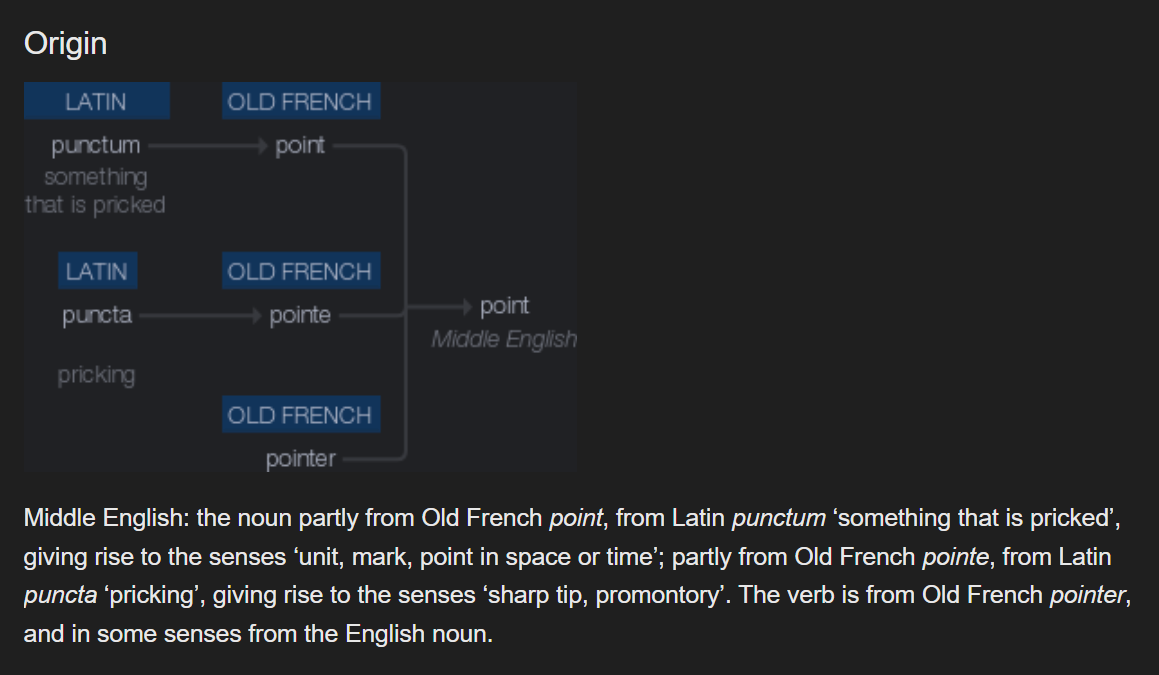

I felt pretty confident that “punctum” was the original word, and that it meant “tip.” I Googled, and I was (mostly) right:

Isn’t etymology fun? (Or isn’t my life sad?)

The reason I bring up this boring/fascinating bit of Francisco trivia is that it came back to me in a very different context a few weeks ago while having dinner with a couple of friends. We were picking the flesh off a meaty piece of gossip concerning a theater company that had been at the center of a public controversy in which two artists had demanded opposite things from it. The two artists in question are queer, and so I said “these gays…” jokingly implying that the problem was their sexuality, not their politics. But one of my friends picked it up and gave it a new spin: “these gays are trying to kill me!”

He was referencing the most famous line of the Mike White series White Lotus (though, like with “Luke, I am your father,” the line has entered the lexicon changed; it is in fact “These gays, they’re trying to murder me”). It was so unexpected that I burst out laughing and continued to do so throughout the night, even when it was inappropriate because we had moved on to different subjects. Why did I find it so funny, I wondered? (There’s a case to be made that I overanalyze my life, but that case will not be heard in this forum, and anyone who makes it will be sent right to jail).

It’s in part because I imagined the artistic director of said company losing her composure and screaming “these gays are trying to kill me!”, a funny image on its own. But it’s deeper than that. My passion for etymology extends to memes, and I am a frequent visitor of knowyourmeme.com; in some ways, memes serve a similar function to words, as their humor relies on connecting disparate situations (a millionaire on a yacht running for her life, an artistic director agonizing over a public statement) by elucidating what they have in common, much like with the two definitions of “point.” It’s like emojis: sometimes you just feel 🫠, and there are no words to convey it better than a yellow blob smiling even as it melts. I can imagine the artistic director texting someone: “these gays are trying to kill me 🫠”

The really curious thing is: I didn’t like the second season of White Lotus, whence this particular meme originates, and I remember being especially put off when the line in question was uttered. It seemed too obvious a pitch for virality (one which the internet nonetheless greenlit), campy in a way that felt unearned — the kind of camp that creators claim when they’ve failed to deliver so their only recourse is to say “it was supposed to be bad — it was camp.”

But now, in the mouth of my friend and applied to this artistic director, I loved it. Had I been wrong about the line? Was it, in fact, good? Or was there something else at play?

To go back to “punctum:” something else I’ve been thinking about recently is that when I was in undergrad, I had to take a semiotics class. What is semiotics, you (a normal person) ask? Semiotics is the kind of field that emerges when people really have nothing better to do and start looking into stuff that may not need looking into (I am not the only one who overanalyzes things). In this case, it’s the study of the relationship between the real world and the ways it is expressed by humans — the relationship between a painting and the thing being painted, for example, or between a word and the thing the word describes. (Google defines it as “the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation,” which makes it sound even more boring).

One of the things I had to do in semiotics class was read Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, a very strange book in which the author does a deep dive into photography — first from a more studious perspective, and then because his mom dies and he desperately tries to “find her” in pictures, whatever that means (the man was grieving). In it—and Imma let Wikipedia take over because I (barely) read this over a decade ago—Barthes develops

the twin concepts of studium and punctum: studium denoting the cultural, linguistic, and political interpretation of a photograph, punctum denoting the wounding, personally touching detail which establishes a direct relationship with the object or person within it.

Or how I like to think about it: the studium of a picture is that which is expected in some way or another, while the punctum is that which is unique to it.

When I write something, the studium of it is the setting, subject, or themes; the other works that I’m pulling from or storytelling traditions that I’m invoking; the relationship that is established with the reader or audience by virtue of the medium; and so on. When I write a play, for example, I’m not inventing playwriting, or the genre of the play, or the conventions of modern-day theater — but even if I was, I’m still not inventing storytelling. And, as I often tell my students (and I’m sure I’ve heard it somewhere else, so I’m not even inventing that) every story has already been told. Influenced by Carl Jung’s archetypes concept, writer Christopher Brooker famously stated there are only seven possible plots, while Joseph Campbell took it further and proclaimed a “monomyth.” But regardless of there being seven or one or a thousand: when it comes to pieces with which to build a story, we’re all pulling from the same bucket (even if we’re not all aware of the same pieces, by virtue of cultural differences or barriers to access).

But that is not a problem, as I also tell my students, because art is not just studium. Once we put the pieces together, we have to breathe life into them, much like God with His figures of clay, or (more applicable when thinking of buckets full of pieces) Dr. Frankenstein with his monster. And what we breathe into it is the punctum, a part of our soul that is meant to puncture through the fourth wall and pierce our audience, “wounding” them into laughing or crying or otherwise emoting in response to a primal recognition with the artist’s point of view. Every story has already been told, but it’s whoever is telling it that makes (or should make) it unique. The scarcity of our market sometimes calls this into question; I’ve had more than one gatekeeper turn my projects down by saying “we’re already doing a play about technology” or “we already have a TV show about immigration in development.” I never know how to respond to that, because obviously they’ve never read Roland Barthes, and a pitch meeting is not the appropriate time to catch them up on it. But what they’re saying is “we already have this studium” and what I’m saying is “yes but you don’t have this punctum because this punctum is me, and I’m gonna tell it my way.”

“Hold on,” you stop me, paying way closer attention to this essay than I thought you would. “If the punctum is you, your own uniqueness, how come it connects with the audience? You’re not the audience, you’re the artist.” Great point. This puzzles me too. In my MFA program, teachers often steered us away from writing broad stories, always pushing us to “make it specific:” specificity, they told us, is what makes something universal. It sounds like nonsense, yet I’ve found it to be true. Some of the stories I love the most have nothing, absolutely nothing to do with me or my life experience: just look at the history of things I’ve recommended in this newsletter. How can I relate to Rosemary’s Baby, a story about a woman in the 1960s feeling no agency over her body? Or Ramy, which chronicles the life of an Egyptian-American family in New Jersey (that most unrelatable of places)? Or The Devil Wears Prada, set so squarely in the world of fashion — what would Miranda say of my all-American Eagle wardrobe? (Probably she’d give me the cerulean monologue). How can I relate to them? How can a personal punctum dwell in a studium that is so foreign to me?

I said earlier that the punctum engenders “a primal recognition” (wow, he quotes himself, what an asshole), and it’s that primality, I think, that explains this phenomenon — as well as my fascination with etymology and memes. “Primal,” I’m guessing, comes from “primo,” which probably means “first” (Google says I’m almost right — it’s “primus,” not “primo,” but it does mean “first”). First what? The first people, I imagine. I think that when I search for the origin of words (even if they mostly, frustratingly, end up in Latin and go back no further), what I’m searching for is the first language, something that connects us all. Something that to me, as a religious person, goes back to God; “religion,” after all, comes from re, “again,” and ligare, “to bind” (as evidenced in words like “ligature” or “ligament” — in Portuguese, a phone call is a “ligação”), suggesting that we used to be connected to something that we are now not. I remember learning in Sunday school that Adam and Eve had “infused science,” a perfect understanding of the world that was given to them directly by God and that was lost when they chose to decide for themselves what was good and what was evil. When I search for the origin of words, I may be trying to get as close as possible to that perfect understanding, that One Knowledge that gives the punctum its universal power.

But even if you’re not religious, the punctum has a reason to remain universal: we can lean instead on Jung. He spoke of the “collective unconscious,” a series of instincts and archetypes that seem to be embedded in the human brain and therefore repeat across space and time:

The existence of the collective unconscious means that individual consciousness is anything but a tabula rasa and is not immune to predetermining influences. On the contrary, it is in the highest degree influenced by inherited presuppositions, quite apart from the unavoidable influences exerted upon it by the environment. The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences, and hence it exerts an influence that compromises the freedom of consciousness in the highest degree, since it is continually striving to lead all conscious processes back into the old paths.

The studium, then, could be likened to “the unavoidable influences exerted upon [us] by the environment,” a.k.a. the present — while the punctum would be “the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings,” a.k.a. the always.

“So what is your point?” you ask impatiently, as you seriously consider giving up on this article and bingeing White Lotus instead. “That ‘these gays are trying to kill me’ is funny because some caveman way back when made that joke around the fire?” Maybe. Not quite. But since we’re talking about cavemen: a few months ago, a friend and I went to dinner with a theater director and proceeded to shit on our MFA program with gusto, which this director found quite funny, saying “you should write a play about it.” On the subway back home, we jokingly threw out ideas for what we imagined would be an insufferable project (who wants to watch a play about an MFA program?), until I suddenly stopped and said: “What if it starts with two cavemen bringing in a bison, then one of them takes some of its blood and paints the hunt onto the cave wall?” We looked at each other excitedly. Maybe we should write it.

If the punctum is the always, the job of the artist is to preserve that always, to keep teaching us that primal language despite more present needs. What practical use is it really, when trying to survive the Ice Age, to stop and paint on a cave wall? It does nothing for the people painting it — but tens of thousands of years later, most of us would agree that the fact the Lascaux cave paintings exist is pretty awesome. It puts us in touch with a time that we cannot possibly imagine by ourselves — and we don’t have to, because it is imagined for us, right there on the wall. It pierces through the stone to make us feel alive, part of something larger, something eternal.

“Okay, bro. But the second season of White Lotus is not the Lascaux cave paintings.” True. And that’s why I didn’t like it. I mean, listen, not everything has to be the Lascaux cave paintings (also, who knows, maybe those were super shit compared to other paintings that never survived; I don’t have enough parameters to judge Paleolithic art). But I found the second season of White Lotus to be too much studium, taking the basic elements of season one (which I recommended) and remixing them in a way that didn’t say anything particularly poignant (another word related to “point” — it comes from pungere, “to prick”). It was only later, once my friend had resignified it, that “these gays are trying to kill me” pierced me with laughter.

Is there any inherent value to the joke? Perhaps, in its ability to comment upon a perception of gay men (mainly, that they are vicious) with exaggeration. But it asks too much of the viewer, in my opinion. On the show, the line rested its humor on who was delivering it and the ridiculousness of her situation, which I guess I didn’t find that funny. For it to live forever, it had to be divorced from its studium and assigned new meaning. Which is often what memes do: I can laugh at “Sure, Jan” even though I’ve never seen A Very Brady Sequel (though I did read this wonderful Vulture explainer) because of Christine Taylor’s pitch-perfect expression. But how much better would it be if the artifact that spun the meme matched its popularity? How much better would it be to be pierced by a whole show instead of just a few seconds of it?

I guess what I’m trying to say is: I need more punctum with my studium. Earlier this year, the New York Times TV critic James Poniewozik coined the term “Mid TV,” which he defined as “what you get when you raise TV’s production values and lower its ambitions:”

It reminds you a little of something you once liked a lot. It substitutes great casting for great ideas. (You really liked the star in that other thing! You can’t believe they got Meryl Streep!)

Mid is based on a well-known book or movie or murder. Mid looks great on a big screen. (Though for some reason everything looks blue.) Mid was shot on location in multiple countries. Mid probably could have been a couple episodes shorter. Mid is fine, though. It’s good enough.

Above all, Mid is easy. It’s not dumb easy — it shows evidence that its writers have read books. But the story beats are familiar. Plot points and themes are repeated. You don’t have to immerse yourself single-mindedly the way you might have with, say, “The Wire.” It is prestige TV that you can fold laundry to.

As anyone who has spent significant time with me can tell you, I refuse to fold laundry to TV; I’m all “phones down, eyes on the screen.” Which is perhaps why I hate everything. As Poniewozik puts it, “We lose something when we become willing to settle (…) A show that can’t disappoint you can’t surprise you. A show that can’t enrage you can’t engage you.” It’s all studium and no punctum. And if there’s not going to be any punctum, we might as well focus on eating the bison and leave the cave wall alone, because art then truly serves no purpose whatsoever other than generating a few snippets that can be turned into a GIF and used for a joke during dinner. Maybe it’s not Mid TV, it’s Meme TV.

The entertainment industry would, of course, disagree with me. There’s a lot of money to be made in people paying a subscription for content to fold laundry to. But I do think the consequences of that are dire. Much like “Mid TV” (a term that caught on really fast because there’s like five TV critics in the country and they all read each other), another expression that has recently entered the lexicon is “slop,” which I first encountered in a New York Magazine article that defined it as “a term of art, akin to spam, for low-rent, scammy garbage generated by artificial intelligence and increasingly prevalent across the internet — and beyond.” The article argued that slop is dangerous because, much like spam, it clogs search results and social media feeds, crowding an already noisy ecosystem with low-quality content. We do not need A.I. to generate slop, by the way; just open Netflix and you’ll find some very sloppy human-generated content — the difference is that A.I. can generate it at a much larger scale.

But the true issue, regardless of who’s slopping, is that, as the article puts it:

[Slop is], it seems, what we want. The other important participants in the slop economy, besides the sloppers and the influencers and the platforms, are all of us. Everyone who idly scrolls through Facebook or TikTok or Twitter on their phone, who puts Spotify on autoplay, or who buys the cheapest recipe book on Amazon is creating the demand.

Operating word: “idly” (this one from the German eitel, “bare, worthless”), as in “watching while I fold laundry.” Mid TV and all its sloppy brethren must engage us when we’re idle, half watching, half listening, half paying attention, half thinking — otherwise we’d reject their worthlessness. But idle is not the same as asleep, or dead. Part of us still absorbs it, enough to remember some of it later during dinner and laugh at the meme. My worry is that slop is not just clogging our feeds and our search engines, but also our brains: I laughed at the meme because it engendered primal recognition — but as it pierced me, it reminded me of how rare that feeling has become.

Poniewozik says “we lose something when we become willing to settle,” which he posits is our ability to feel. I’d go further: what if what we’re giving up when we give up on punctum is our access to that primal language of our ancestors, the collective unconscious that keeps us all tethered?

The Bible (I know, I know, I’m almost done, I promise) has a very famous story about language. It’s short, so let’s hear it from the English Standard Version:

Genesis 11: Now the whole earth had one language and the same words. 2 And as people migrated from the east, they found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. 3 And they said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. 4 Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be dispersed over the face of the whole earth.” 5 And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of man had built. 6 And the Lord said, “Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do. And nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. 7 Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, so that they may not understand one another's speech.” 8 So the Lord dispersed them from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. 9 Therefore its name was called Babel, because there the Lord confused[a] the language of all the earth. And from there the Lord dispersed them over the face of all the earth.

[a] According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica, Babel sounds like the Hebrew word balal, “to confuse”

My immediate response to the story is: Why did God curse them? It sounds like insecurity (“nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them”). But that can’t be; not only does that not square with the Bible’s idea of a perfect God, it’s also incongruent with the resolution of the story — since, after all, He was powerful enough to stop the builders, and is therefore objectively superior to them: no reason to be insecure. (Also, unrelated: who is God talking to when he says “behold” and “come, let us?” Himself? Is He weird like me?)

I imagine, then, that it was humanity’s aims He took objection to, the thing humans had decided to put their power towards. As I look around, I see slop coming from multiple towers that are trying to reach to the heavens: streaming, social media, A.I., e-commerce. Tech bros that fashion themselves into gods. The curse repeats itself: the more the towers grow, the more they spew their toxic goop, invading our brains and overwhelming us into submission by sheer boredom, making us forget that we used to have “one language and the same words.” We drown in studium and lose our ability (or, idle as we are, we even lose our will) to be pricked by punctum. We stop speaking to the cavemen and make no meaningful efforts to leave anything for the humans of the future. The Babel towers builders pay too well, as the Times put it in another article, “How Everyone Got Lost in Netflix’s Endless Library:”

There’s no denying that, in the long journey prestige TV has taken from “The Wire” to “The Bear,” a certain slackness has crept in: comedies without many jokes, dramas without any stakes, a pronounced preference for backward-looking plotting that fixates on characters’ traumas, a plague of visibly Canadian filming locations, “Barry.” The first generation of prestige shows was created by veterans of linear TV who longed for creative freedom but knew the rudiments of the business, the things that kept you watching through the commercial breaks: pacing, structure, believable dialogue. But the leash has been off for a decade now (…) When you’re drowning in cash, it’s always tempting to say yes.

I read a while ago (in an article I can’t find, so if you do send it to me) that George Orwell’s 1984 (which I have read and loved) was not as accurate in its prediction of a future as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (which is in my queue and I will hopefully read soon). 1984 imagines a world in which the population is controlled via a rigidly centralized system of information that allows for immediate censorship and twisting of facts to fit the government’s narrative; Huxley, on the other hand, posits that the true danger is not too little information, but rather too much — that by giving people as many distractions as possible, they’ll have no reason to rise against their oppressors. Idleness may be a feature, not a bug.

The polarization that our current towers of Babel have engendered makes us speak different languages, even if metaphorically, assigning different meanings to the same words—one person’s “gaslighting” is another person’s “speaking the unpopular truth.” So it’s easy to become frightened at the thought that one of the narratives will win over the other and proceed to squash dissent in a 1984-like fashion. But perhaps it’s just as frightening to imagine that it could all, as they say in Brazil, “end in pizza.” The towers that are currently being erected will no doubt collapse in the same bubble-bursting that took so many industries before them — and when they fall, and their makers disperse, what will happen to the rest of us, deprived of the slop that made our idleness possible, and without access to the primal language of our ancestors to connect us? What will pierce us with laughter and sadness and other emotions then? We might be, in effect, turned into slop ourselves, faces that idly smile even as we melt.

I leave, then, you with a final quote, bummerish as it may be, by Frankenstein’s monster (the OG slop) at the end of his murderous vengeful rampage:

I shall collect my funeral pile and consume to ashes this miserable frame, that its remains may afford no light to any curious and unhallowed wretch who would create such another as I have been. I shall die. I shall no longer feel the agonies which now consume me or be the prey of feelings unsatisfied, yet unquenched. He is dead who called me into being; and when I shall be no more, the very remembrance of us both will speedily vanish. I shall no longer see the sun or stars or feel the winds play on my cheeks. Light, feeling, and sense will pass away; and in this condition must I find my happiness. Some years ago, when the images which this world affords first opened upon me, when I felt the cheering warmth of summer and heard the rustling of the leaves and the warbling of the birds, and these were all to me, I should have wept to die; now it is my only consolation. Polluted by crimes and torn by the bitterest remorse, where can I find rest but in death?